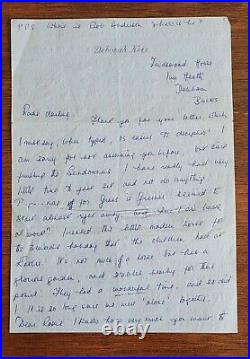

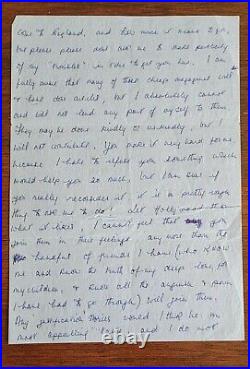

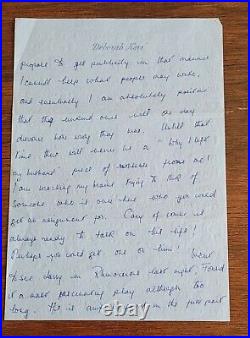

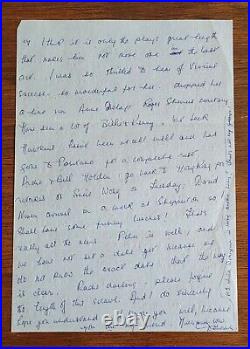

A FANTASTIC 2PP 7 1/4 X 10 1/4 INCH PAPER HANDWRITTEN ON FRONT AND BACK OF BOTH PAGES OF A DEBORAH KERR LETTER ON HER PERSONAL LETTERHEAD PAPER. A VERY DETAILED PERSONAL LETTER. MENTIONS HER MOVIES AND, ANY OTHER ACTORS SHE WORKED WITH. Deborah Jane Trimmer CBE, known professionally as Deborah Kerr, was a British film, theatre, and television actress. She was nominated six times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, and holds the record for an actress most nominated in the lead actress category without winning. British actress Kerr dies at 86. Deborah Kerr was born Deborah Jane Trimmer in 1921. British actress Deborah Kerr, known to millions for her roles in The King And I, Black Narcissus and From Here To Eternity, has died at the age of 86. Born in Scotland in 1921, the actress made her name in British films before becoming successful in Hollywood. Nominated for the best actress Oscar six times, she was given an honorary award by the Academy in 1994. Kerr, who had suffered from Parkinson’s disease for a number of years, died in Suffolk on Tuesday, her agent said. An artist of impeccable grace and beauty. She leaves a husband, the novelist and screenwriter Peter Viertel, two daughters and three grandchildren. Kerr began her career in regional British theatres and entertained the troops during World War II. Her first major screen role came in 1941’s Major Barbara, while her last came in 1985’s The Assam Garden. Between them she appeared alongside such Hollywood icons as Burt Lancaster, Cary Grant and Robert Mitchum. Despite six nominations her only Oscar was an honorary one. Notable British films include The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, in which she played three roles, and Black Narcissus, which saw as a nun in the Himalayas. She remains best known, however, for her torrid sex scene with Lancaster in From Here to Eternity and for dancing with Yul Brynner in The King and I. From the late 1960s onwards she concentrated on theatre and television roles. Kerr always played down her success, attributing it to her having had “an awful lot of luck”. Her honorary Oscar came in recognition of “an artist of impeccable grace and beauty, a dedicated actress whose motion picture career has always stood for perfection, discipline and elegance”. “I must confess, I’ve had a marvellous time, ” she said as she collected the statuette. DEBORAH Kerr, who has died at the age of 86, was without doubt one of the greatest film stars ever to come out of Scotland. She famously rolled in the surf with Burt Lancaster in From Here to Eternity (1953), she could have danced all night with Yul Brynner in the musical The King and I (1956) and was nominated for the best actress Oscar on no fewer than six different occasions. Six nominations without a single win is a bitter-sweet record in the Oscar history books, but they remain a fantastic achievement in themselves. The Academy finally gave her an honorary award in 1994 and the citation captured the essence of her qualities over almost half a century on the big screen, describing her as “an artist of impeccable grace and beauty”. Despite the distinctive red hair, Kerr is less readily recognised as a Scot than Sir Sean Connery, certainly less universally recognised. She left her homeland at a young age and was repeatedly cast as an English rose. She is more readily associated with the prim governess of The King and I and the crippled, self-sacrificing heroine to Cary Grant’s hero in An Affair to Remember (1957), than she is with the lusty, adulterous wife in From Here to Eternity, even though that surf scene is one of the most famous in the history of the movies. Toss in a couple of nuns and it is no surprise that Kerr’s enduring image has been one of dignity and serenity. But her resume is punctuated with roles that illustrate her range and her readiness to tackle challenging material. In one of her earliest films, Love on the Dole (1941), she was a Lancashire mill girl who succumbs to the overtures of a rich admirer after the death of her sweetheart. It was made two decades before such issues were addressed by the kitchen-sink dramas and social realist cinema. Twenty-eight years later she showed her chutzpah and much else besides when she stripped off for Elia Kazan’s The Arrangement, another tale of adultery, co-starring Kirk Douglas and Faye Dunaway. Kerr was in her late forties by this point, at a time when nudity was still relatively unusual in Hollywood films. The daughter of a civil engineer, she was born Deborah Jane Kerr-Trimmer in 1921 in a nursing home in Glasgow. She spent her earliest years in Helensburgh, routinely cited as her place of birth. She trained as a dancer initially at her aunt’s school in Bristol and made her debut with Sadler’s Wells Ballet while in her teens. But she soon turned to drama, had a short spell with a repertory company in Oxford and made her film debut in Powell and Pressburger’s wartime thriller Contraband (1940), though her scenes were cut out. Powell and Pressburger made amends by giving her no fewer than three starring roles in their classic 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, an epic and, at the time, controversial celebration of British military pluck, honour and eccentricity. The film spans the era from the Boer War to the Second World War. Kerr is the woman who officer Roger Livesey loves and loses (to a German officer, no less), and she also plays two further women who attract his attention further down the line. By that time, Kerr had had starring roles in Love on the Dole and an adaptation of A J Cronin’s Hatter’s Castle (1942), in a rare role as a Scot, but Blimp put her very much centre stage and showcased both her beauty and her talent. Having served up three variants on the idealised sweetheart in Blimp, she played a nun in Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus (1947) before heading for Hollywood. She secured her first Oscar nomination as Spencer Tracy’s alcoholic wife in Edward, My Son (1949) and appeared in such glittering blockbusters as King Solomon’s Mines (1950), Quo Vadis (1951), The Prisoner of Zenda (1952) and Julius Caesar (1953), alongside the young Marlon Brando. But it was From Here to Eternity that propelled her to the very top ranks of Hollywood actresses. After From Here to Eternity and The King and I, further Oscar nominations followed for Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1957), Separate Tables (1958) and The Sundowners (1960). But the quality of Kerr’s films fell away rather badly in the 1960s and she virtually retired at the end of the decade. In 1997 she was made a CBE. Kerr was seen as easy to work with, but she said: I’m neat and tidy. I hate it when things are a mess. You could say I’m neat and tidy inside and out. I’ve never played a slut, although I was a bit ruffled in The Sundowners. In 1945, Kerr married Anthony Bartley, who she had met when he was a squadron leader in the Royal Air Force. They had two daughters and divorced in 1959. A year later, she married Peter Viertel, a novelist-screenwriter. She is survived by Viertel and two daughters from her first marriage. Full name, Deborah Jane Kerr-Trimmer; born September 30, 1921, in Helensburgh, Scotland; immigrated to the United States, 1947; daughter of Arthur Charles(a civil engineer) and Kathleen Rose (Smale) Kerr-Trimmer; married Anthony Charles Bartley, November 28, 1946 (divorced, July, 1959); married Peter Viertel (a screenwriter), July 23, 1960; children: Melanie, Francesca, and one step daughter. Addresses: AGENT–The Lantz Office, 9255 Sunset Blvd. Suite 505, Los Angeles, CA 90069. Deborah Kerr’s stage and screen career spans more than four decades, during which she has appeared in over forty-five films. She has won four New York Film Critics’s best actress awards and six Academy Award nominations–for Edward, My Son, From Here to Eternity, The King and I, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, Separate Tables, and The Sundowners. She has yet to win an Oscar and admits she minds missing out on the one in 1960 for Ida, the deprived but tolerant wife of Robert Mitchum’s itinerant Australian sheep farmer in The Sundowners. Yet, despite her enduring appeal, according to Ken Doeckel in the Films in Review issue of January, 1978, Kerr still defies classification today. All her gifts–classically chiseled features, expressive voice, charm, wit, intelligence and literacy–serve to challenge the usual Hollywood actress image. Trained as a dancer at her aunt’s drama school in Bristol, England, Kerr wona scholarship to the Sadler’s Wells ballet school and at seventeen made her London debut among the corps-de-ballet in Prometheus. She soon discovered, however, that she was more interested in drama and began playing small roles invarious Shakespearean productions. In the early 1940s, she made her British film debut as the Salvation Army girl, Jenny Hill, in the movie version of George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara. Other film roles followed in which she typically played cool and reserved well-bred ladies. In 1946, on the strength ofher sensitive portrayal of a nun in Black Narcissus, she was brought to Hollywood by Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer to play the lead opposite Clark Gable in The Hucksters. She retained her serene, ladylike image on the American screen through a series of genteel roles in such films as If Winter Comes, Young Bess, King Solomon’s Mines, and Quo Vadis. Then in 1953, she was given the opportunityto play, on loan to Columbia, the part of Karen Holmes, the alcoholic nymphomaniac Army wife in From Here to Eternity. Her scene on the beach with Burt Lancaster in their classic love scene from that movie made it clear that a real woman existed beneath that cool exterior. “Suddenly I could act, ” Kerr toldRichard Lee in an interview that appeared in the January 25, 1975, New YorkPost. Suddenly I had sex appeal. Soon thereafter Kerr made her Broadway debut as Laura Reynolds, the compassionate wife in Robert Anderson’s Tea and Sympathy. The part looked like just another “teacup” role, she related to Lee, another goody-goody lady. ” It tookdirector Elia Kazan, Kerr explained, to show her that Laura was “a symbol ofso many things that I myself believe in. Compassion and tenderness, forinstance, and the idea that a man need not conform to a schoolboy image of masculinity to be a man. Kerr’s sensitive, dazzling performance won both critical and popular acclaim. She remained a full season with the hit drama and later went on a national tour with it. Following Tea and Sympathy, Kerr became an internationally respected star. Among her most notable film performances of the next decade were those in The King and I, Tea and Sympathy, Separate Tables, Beloved Infidel, and the Australian-filmed The Sundowners. She was also the tormented governess in an adaptation of Henry James’s novella Turn of the Screw titled The Innocents, an unconventional governess in The Chalk Garden, the frustrated spinster awakened tolife by Richard Burton in The Night of the Iguana, and Kirk Douglas’s unsatisfied wife in The Arrangement. Since then she has appeared in numerous other plays, anmong them Edward Albee’s Seascape, Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, and Shaws’s Candida. Kerr made her television debut in the BBC production Three Roads to Rome. Other television appearances have included roles in Witness for the Prosecution, A Woman ofSubstance, and Reunion at Fairborough. The actress has also graced a few Oscar broadcasts, hosted the Tony Awards in 1972, and narrated several documentaries. STAGE DEBUT–Harlequin, Harlequin and Columbine, Knightstone Pavilion, Weston-Super-Mare, U. LONDON DEBUT–In the corps de ballet, Prometheus, Sadler’s Wells Opera House, 1938. BROADWAY DEBUT–Laura Reynolds, Tea and Sympathy, Ethel Barrymore Theatre, September 30, 1953. Credits; PRINCIPAL STAGE APPEARANCES. Appeared in repertory, various Shakespeare plays, Open Air Theatre, Regents Park, London, 1939. Margaret, Dear Brutus and Patty Moss, The Two Bouquets, both with the Oxford Repertory Theatre, Oxford Playhouse, U. Ellie Dunn, Heartbreak House, Cambridge Theatre, London, 1943. Edith Harnham, The Day After the Fair, Lyric Theatre, London, 1972. Nancy, Seascape, Shubert Theatre, New York City, then Shubert Theatre, Los Angeles, 1974-75. Julie Stevens, Souvenir, Shubert Theatre, Los Angeles, 1975. Mary Tyrone, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Ahmanson Theatre, Los Angeles, 1977. Title role, Candida, Albery Theatre, London, 1977. Title role, The Last of Mrs. Cheney, Eisenhower Theatre, Kennedy Center, Washington, DC, 1978. Overheard, London production, 1981. The Corn Is Green, London production, 1985. Ellie Dunn, Heartbreak House, U. Manningham, Angel Street, Holland, Belgium, France, for ENSA, 1945. Laura Reynolds, Tea and Sympathy, U. Edith Harnham, The Day After the Fair, U. FILM DEBUT–Hatcheck girl, Contraband, British National, 1939. Credits; PRINCIPAL FILM APPEARANCES. Jenny Hill, Major Barbara, Universal, 1940. Love on the Dole, Universal, 1940. Penn of Pennsylvania, British National, 1940. Hatter’s Castle, 1941. The Day Will Dawn, Denham, 1941. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, United Artists, 1945. I See a Dark Stranger, 1945. Black Narcissus, Universal, 1946. The Hucksters, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), 1947. If Winter Comes, MGM, 1947. The Adventuress, Eagle-Lion, 1947. Hatter’s Castle, Paramount, 1948. Edward, My Son, MGM, 1949. King Solomon’s Mines, MGM, 1950. Please Believe Me, MGM, 1950. Quo Vadis, MGM, 1951. Rage of the Vulture, 1951. Prisoner of Zenda, MGM, 1952. Young Bess, MGM, 1953. Dream Wife, MGM, 1953. Julius Caesar, MGM, 1953. Thunder in the East, Paramount, 1953. Karen Holmes, From Here to Eternity, Columbia, 1953. The End of the Affair, Columbia, 1955. Tea and Sympathy, MGM, 1956. The Proud and the Profane, Paramount, 1956. The King and I, Twentieth Century-Fox, 1956. Allison, Twentieth Century-Fox, 1957. An Affair to Remember, Twentieth Century-Fox, 1957. Separate Tables, Universal, 1958. Bonjour Tristesse, Columbia, 1958. Count Your Blessings, MGM, 1959. The Journey, MGM, 1959. Beloved Infidel, Twentieth Century-Fox, 1959. Ida, The Sundowners, Warner Brothers, 1960. The Grass Is Greener, Universal, 1960. The Innocents, Twentieth Century-Fox, 1961. The Naked Edge, United Artists, 1961. The Chalk Garden, Universal, 1964. The Night of the Iguana, MGM, 1964. Marriage on the Rocks, Warner Brothers, 1965. Casino Royale, Columbia, 1967. The Eye of the Devil, MGM, 1967. The Gypsy Moths, MGM, 1969. The Arrangement, Warner Brothers, 1969. The Assam Garden, Moving Picture Company, 1985. TELEVISION DEBUT–Moira Shepleigh, Grace Annesly, and Miranda Watney, Three Roads to Rome, BBC, 1961. Credits; PRINCIPAL TELEVISION APPEARANCES; MOVIES. A Song at Twilight, 1981. Witness for the Prosecution, 1982. Ann & Debbie, 1984. Reunion at Fairborough, Home Box Office, 1985. MINI-SERIES A Woman of Substance, syndicated, 1985. Emma Harte, Hold the Dream, syndicated, 1986. Deborah Kerr, CBE was a Scottish stage, television and film actress. She won the Sarah Siddons Award for her Chicago performance as Laura Reynolds in Tea and Sympathy, a role which she originated on Broadway, a Golden Globe Award for the motion picture, The King and I, and she was also the recipient of honorary Academy, BAFTA and Cannes Film Festival awards. She was nominated six times for an Academy Award as Best Actress but never won. In 1994, however, she was cited by the Academy for a film career that always represented “perfection, discipline and elegance”. Her films include The King and I, An Affair to Remember, From Here to Eternity, Quo Vadis, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison and Separate Tables. Although the Scottish pronunciation of her surname, is closer to a phonetic reading of the name, when she was being promoted as a Hollywood actress it was made clear that her surname should be pronounced the same as “car”. In order to avoid confusion over pronunciation, Louis B. Mayer of MGM billed her as Kerr rhymes with Star! Kerr was born Deborah Jane Kerr-Trimmer in a private nursing home in Glasgow, Scotland, the only daughter of Kathleen Rose and Capt. Arthur Charles Kerr-Trimmer, a World War I veteran pilot who later became a naval architect and civil engineer. Directly after her birth she spent the first three years of her life in the nearby town of Helensburgh, where her parents lived with Deborah’s grandparents in a house on West King Street. Kerr had a younger brother, Edward, who became a journalist and died in a’road-rage’ incident in 2004. English actress who received an honorary Academy Award in 1994 for being a dedicated actress whose motion picture career has always stood for perfection, discipline and elegance. Name variations: christened Deborah Kerr-Trimmer, always acted under the name Deborah Kerr, and kept her maiden name through two marriages. Born Deborah Jane Kerr-Trimmer in Helensburgh, Scotland, on September 30, 1921, but grew up mainly in England; only daughter of Arthur Kerr-Trimmer (a civil engineer and architect); trained as a dancer at her aunt Phyllis Smale’s drama school in Bristol; granted a scholarship to Sadler’s Wells ballet school; married Anthony Charles Bartley (an aviator), on November 28, 1945 (divorced 1959); married Peter Viertel (a writer), in 1959; children: (first marriage)Melanie Jane Bartley; Francesca Bartley. Made BBC radio debut (1936); made London stage debut (1939); shot first film (1941); shot first Hollywood film, The Hucksters (1947). Major Barbara (UK, 1941); Love on the Dole (UK, 1941); Penn of Pennsylvania Courageous Mr. Penn, UK, 1941; Hatter’s Castle (UK, 1941); The Day Will Dawn (UK 1942); The Avengers (UK, 1942); The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (UK, 1943); Perfect Strangers (Vacation from Marriage, UK, 1945); I See a Dark Stranger (The Adventuress, UK, 1946); Black Narcissus (UK, 1947); The Hucksters (1947); If Winter Comes (1948); Edward, My Son (1949); Please Believe Me (1950); King Solomon’s Mines (1950); Quo Vadis (1951); The Prisoner of Zenda (1952); Thunder in the East (1953); Young Bess (as Catherine Parr, 1953); Julius Caesar (1953); Dream Wife (1953); From Here to Eternity (1953); The End of the Affair (UK, 1955); The Proud and the Profane (1956); The King and I (1956); Tea and Sympathy (1956); Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957); An Affair to Remember (1957); Bonjour Tristesse (UK, 1958); Separate Tables (1958); The Journey (1959); Count Your Blessings (1959); Beloved Infidel (asSheilah Graham, 1959); The Sundowners (1960); The Grass is Greener (1960); The Naked Edge (1961); The Innocents (1961); The Chalk Garden (1963); The Night of the Iguana (1964); Marriage on the Rocks (1965); Eye of the Devil (1967); Casino Royale (1967); Prudence and the Pill (UK, 1968); The Gypsy Moths (1969); The Arrangement (1969); A Woman of Substance (1984); The Assam Garden (1985); Reunion at Fairborough (1985); Hold the Dream (1986). In the early years of her movie career, British actress Deborah Kerr played the part of distinguished ladies, and she was a staple figure in the historical epics of the 1950s. Occasionally, she was cast against type and demonstrated that she was an actress of genuine range and ability. One of her most notable roles was as the adulterous officer’s wife in From Here to Eternity (1953). Her famous frolic in the surf with Burt Lancaster tested Hollywood’s skittishness about sex, and paved the way for bolder sensuality in the future, so that by the time she acted in film roles in the late 1960s she was required by some scripts to appear naked. Deborah Kerr-Trimmer was born in Scotland on September 30, 1921, but grew up mainly in England, having an unhappy childhood at joyless boarding schools but conceiving early the ambition to be an actress. Her father was a disabled veteran of the British army who had lost a leg in the trenches of the First World War and worked as the inventor of mechanical gadgets; he died when she was only 16. From her dismal boarding school, she went to a much more likeable drama school run by her aunt Phyllis Smale in Bristol in 1936; the same year, she was auditioned by the British Broadcasting Corporation as a reader. Her polished elocution won her a position reading children’s stories on the air for the next few years. In 1938, then in her late teens, Kerr studied ballet at the Sadler’s Wells Company in London, but at 5’7 she was too tall to become a prima ballerina. She realized, besides, that she did not have the kind of outstanding talent and dancing ability necessary to make her a star. Kerr’s radio work helped her make contacts in the theater world, however, and she had her London stage debut in 1939, moving to the prestigious West End the following year in Heartbreak House. Staying in London despite the hazards of the German bombing, then at its height, she met a Hungarian film director, Gabriel Pascal, who gave her a small role in his superb film of George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara (1941). Her role was that of Jenny Hill, a morally resolute Salvation Army woman; to prepare for the role, the director told Kerr to spend a few weeks working with the real Salvation Army. She found their work serving food and giving shelter to the destitute of London inspiring, but found her own religious inclinations better served by Christian Science, which she studied ardently in the early 1940s. Major Barbara was a success, and Kerr spent the rest of the war years acting in other films by Pascal and his friends. Her second role was as Sally Hardcastle in Love on the Dole, based on a popular novel about life in Britain’s industrial north during the Great Depression. Other roles followed, including Hatter’s Castle (1941), where she was matched with James Mason, and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), in which she proved her versatility by playing three different roles. While filming The Day Will Dawn, where she had the unlikely role of a Norwegian seacaptain’s daughter, she and Rex Harrison, who had joined the cast for a social drink at the end of a day’s work, were almost killed by a German bomb. Despite a terrible scare and concussion, they emerged with nothing worse than scratches and a coating of dirt from the adjacent vegetable garden where the bomb had exploded. In the last year of the war, Kerr joined a theater company which performed Gaslight at British army camps in Western Europe following the D-Day invasion. In 1945, she married Anthony Bartley, a Royal Air Force squadron leader and hero of the Battle of Britain, who had shot down 15 enemy planes. By then, she was fully established as a major figure in British film and theater. In Rumer Godden’s Black Narcissus, her first postwar film, Kerr played the Sister Superior at a bewitched convent in a remote part of the Himalayan mountains, where one of her flock falls in love with an Englishman who lives nearby. The film traces the Sister Superior’s transition from spiritual pride to genuine humility. Acclaimed by many American critics, the movie won the New York Film Critics Award and prompted Louis Mayer, head of MGM, to offer her a Hollywood contract. Not all American reviewers were impressed. The acerbic James Agee wrote: The head nun, Deborah Kerr, just makes Sisterly sheep’s eyes at [the man] as he lunges around the sanctuary in his shorts. Kerr and her husband, who was willing to give up his job as a test pilot and aviation promoter to accompany her to stardom, emigrated from England during the bitter winter of 1946-47, when wartime rationing was still in force. She was dazzled by the opulence of New York, the luxury of the trains, and the splendid way of life in Hollywood, and said she had not eaten so well in all her life. Her first MGM role was as an advertising executive’s wife in The Hucksters (1947), where she played alongside Clark Gable, Ava Gardner, and Sydney Greenstreet. Kerr followed with If Winter Comes (1948), and then Edward, My Son (filmed back in England, 1949) in which she costarred with Spencer Tracy and played the role of a deceived woman descending into alcoholism. In these years, Kerr also gave birth to two daughters but managed to juggle filming schedules around her pregnancies. Despite her success in playing a heavy drinker in Edward, My Son, MGM mainly reserved her for ladylike parts, and in the 1950s she adorned a long succession of historical epics, usually as the wife of a king or an emperor. Among these were Quo Vadis (1951), Young Bess-in which she played Henry VIII’s last wife, Catherine Parr -(1952), and Julius Caesar (1953), playing Portia opposite James Mason’s Brutus. These were the years when British and American actors appeared unselfconsciously side by side, despite the clash of national and regional accents. Allenberg persuaded the producers at Columbia to cast her in the role of Karen Holmes, an unfaithful and libidinous army wife in the film version of James Jones’ popular novel From Here to Eternity, which was then being planned. The role had originally been offered to Joan Crawford, but the temperamental star disliked many aspects of the planned production and withdrew, so Allenberg was able to get the role for Kerr, even though it meant a complete change in the film persona she had exhibited since coming to America. Now, says her biographer Eric Braun, she was transformed into the American conception of how a sexy blonde should look. Marilyn Monroe was currently at her peak in films like River of No Return. And some of the publicity stills of Deborah Kerr at that time could actually be taken for Monroe herself. The film, one of the first to criticize the American army, was a terrific success, and Kerr was highly praised for her convincing role, winning an Oscar nomination. A reddish-blond with noble features, [Deborah] Kerr possessed a quiet glamour that had nothing to do with Hollywood’s definition. It ran for more than a year before making a successful national tour, with Kerr in the leading role throughout. Like From Here to Eternity, the play broke new ground by portraying sympathetically the affair of a mature woman with a teenaged boy at a repressive boarding school. Now independent of the studio system and at the height of her fame and powers, Kerr could vary her work by choosing occasional movie roles which took her fancy. She explained to an interviewer when she left MGM: In the future, parts I choose are going to be about real women; they may not be pleasant, but they will be real people. ” One such “real person was Sarah Miles, her role in the film version of Graham Greene’s novel The End of the Affair, which was released in 1955. Greene himself had worked on several films and wrote movie reviews for the English press but usually deplored the results when his own novels were filmed. This one he gave relatively high praise by saying that it was the “least unsatisfactory, ” adding that “Deborah Kerr gave an extremely good performance” but that her good work was destroyed by the miscasting of Van Johnson to play a man who was meant to be much older. Another great success was The King and I (1956), a corny musical adaptation of English governess Anna Leonowens’ memoirs about her life as tutor to the king of Siam’s children. Yul Brynner played the king, after a four-year run on stage in the same part had brought him stardom. Kerr was a reasonably good singer, but she had a voice-double in the film, Marni Nixon, who filled in on the sustained high notes and complicated passages. The next year, Kerr was paired with Robert Mitchum in John Huston’s film Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, again playing a nun, as she had in Black Narcissus. This time, she was cast adrift in a lifeboat with a tough marine in the middle of the Pacific War, surviving through a savvy combination of divine and mundane ideas and beating a Japanese army into the bargain. As film historian Brandon French notes, the film was in some ways a rehash of Huston’s earlier success The African Queen, but whereas the Katharine Hepburn figure had been on terms of full equality with her man in facing jungle hazards, Kerr now played a far more passive role. French suggests that the shift symbolizes the cramping social restriction many American women felt in the 1950s. In the same year, 1957, Kerr made An Affair to Remember, a classic “weepie” with Cary Grant, which was recently parodied in the Tom Hanks-Meg Ryan film Sleepless in Seattle. Kerr’s marriage to Anthony Bartley had become strained during the 1950s as she toured with plays or filmed on location. To compound their long separations, he had become a European representative of CBS television. Rumors of infidelities in the press heralded their divorce. In 1959, but gossip columnists found Kerr far more private and self-contained than many of the stars and her divorce correspondingly less sensational. In 1960, after success in an Australian film, The Sundowners, in which she was again paired with Mitchum, Kerr married Peter Viertel, a writer who had worked on the script of her 1959 film The Journey and was the son of Salka Viertel. Throughout the 1960s, Kerr and her husband lived mainly in his home country, Switzerland, where she enjoyed publicity as a prominent member of the “jet set, ” flying frequently back and forth to New York, Hollywood, London, and Paris, when the idea of flying still seemed more romantic than irksome. In The Innocents (1961), based on Henry James’ story The Turn of the Screw, Kerr won high praise from The New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, who wrote: Deborah Kerr’s performance is in the grand manner-as modulated and controlled, and yet as flamboyant, as almost anything you’ll see on the stage. And it’s a tribute to Miss Kerr’s beauty and dramatic powers that, after twenty years in the movies-years of constant overexposure-she is more exciting than ever. ” Kerr herself felt it was one of her best films but added to an interviewer: “It was also one of the hardest; in a very long schedule I was in virtually every shot [and I] worked every single day of the sixteen week schedule. By contrast, her later films of the 1960s, when cinema was coming under intense competitive pressure from television, were less compelling. In Night of the Iguana (1964), a film based on Tennessee Williams’ play in which Kerr played “a frustrated spinster awakened to life by Richard Burton, ” remarks one critic, The production publicity for the film so far exceeded what emerged on the screen that everything about the film, including Deborah’s neurotic performance, was a disappointing anticlimax. The film, which also starred Elizabeth Taylor, Ava Gardner, and Sue Lyon, was shot on location at Puerta Villarta in Mexico and directed by John Huston, who had to overcome great technical and logistical difficulties to finish the production at all. Kerr, who was paid a quarter of a million dollars for her role, wrote for Esquire magazine an ironic article about the difficulties the production faced, in which she deplored efforts by the press to whip up false tales of feuding and adultery among the cast. In the late 1960s, film nudity came into fashion as the censorious Production Code which had kept a puritanical ban on film sex breathed its last. By then, Kerr was 47 but willingly shed her clothes for The Gypsy Moths, a parachuting film, and then for The Arrangement (1969), director Elia Kazan’s adaptation of his own bestselling novel. The Arrangement proved to be her last movie role before a 15-year retirement. Playing the wife of a Los Angeles advertising executive (Kirk Douglas), Kerr, sounding as English as ever, was miscast. Deploring the result, Pauline Kael wrote one of the most stinging reviews Kerr had ever received. Deborah Kerr is wrong in every nuance as a conventional Los Angeles matron. She’s even less at home than she was as the adulterous Kansas housewife in The Gypsy Moths. The understanding-unloved-wife role she plays here (and she’s hideously made up) wears out an actress’s welcome faster than anything else; it just about convinced me that I didn’t ever want to see her again. Miss Kerr used to play against her overemotional voice; now she lets it use her for a constant neurotic nagging that is revolting. In view of Kael’s eminence and her earlier praise for Kerr’s work in The Innocents, this review probably carried a particularly sharp sting. Kerr claimed to have enjoyed making the film, but this and other negative reviews must have convinced her that the time had come to quit. She took a “leave of absence, ” saying she felt “too young or too old” for any role offered. Kerr showed in the following years that she still had plenty of resilience, however. Her increasing leisure time was spent with her husband and friends in Switzerland and a new home in Marbella, Spain. During her film career, Deborah Kerr was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actress a record-breaking six times; no other actress had had the misfortune to be nominated so many times without winning. But nominations are cherished compliments from the Hollywood community, and she had been singled out for her performances in Edward, My Son, The King and I, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, From Here to Eternity, Separate Tables, and The Sundowners. In March 1994, as she was awarded an honorary Oscar at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the 72-year-old Kerr received a standing ovation. “Thank you, thank you, ” she said, obviously moved. There should be some more words for thank you, shouldn’t there. Poised patiently center stage, in frail health, Kerr once again lent her grace and dignity to the world of the movies, contributing the most touching moment of the evening. Agee on Film: Reviews and Comments. Mornings in the Dark. I Lost it at the Movies. The MGM Stock Company: The Golden Era. New Rochelle, NY: 1973. On the Verge of Revolt: Women in American Films of the Fifties, 1958. Patrick Allitt, Professor of History, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Deborah Jane Trimmer[1] CBE (30 September 1921 – 16 October 2007), known professionally as Deborah Kerr /k?? R/, was a British film, theatre, and television actress. During her international film career, Kerr won a Golden Globe Award for her performance as Anna Leonowens in the musical film The King and I (1956). Her other films include The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Black Narcissus (1947), From Here to Eternity (1953), Tea and Sympathy (1956), An Affair to Remember (1957), Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957), Separate Tables (1958), The Sundowners (1960), The Innocents (1961), The Grass is Greener (1960), and The Night of the Iguana (1964). In 1994, having already received honorary awards from the Cannes Film Festival and BAFTA, Kerr received an Academy Honorary Award with a citation recognising her as “an artist of impeccable grace and beauty, a dedicated actress whose motion picture career has always stood for perfection, discipline and elegance”. Early theatre and film. From Here to Eternity and Broadway. Peak years of stardom. Deborah Jane Trimmer[1] was born on 30 September 1921 in Hillhead, Glasgow, [3] the only daughter of Kathleen Rose (née Smale) and Capt. Arthur Charles Kerr Trimmer, a World War I veteran and pilot who lost a leg at the Battle of the Somme and later became a naval architect and civil engineer. Trimmer and Smale married, both aged 28, on 21 August 1919 in Smale’s hometown of Lydney, Gloucestershire. Young Deborah spent the first three years of her life in the west coast town of Helensburgh, where her parents lived with Deborah’s grandparents in a house on West King Street. Kerr had a younger brother, Edmund (“Teddy”), who became a journalist. He died, aged 78, in a road rage incident in 2004. Kerr was educated at the independent Northumberland House School, Henleaze in Bristol, and at Rossholme School, Weston-super-Mare. Kerr originally trained as a ballet dancer, first appearing on stage at Sadler’s Wells in 1938. After changing careers, she soon found success as an actress. Her first acting teacher was her aunt, Phyllis Smale, who worked at a drama school in Bristol run by Lally Cuthbert Hicks. [8][9] She adopted the name Deborah Kerr on becoming a film actress (“Kerr” was a family name going back to the maternal grandmother of her grandfather Arthur Kerr Trimmer). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: “Deborah Kerr” – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message). Kerr’s first stage appearance was at Weston-super-Mare in 1937, as “Harlequin” in the mime play Harlequin and Columbine. She then went to the Sadler’s Wells ballet school and in 1938 made her début in the corps de ballet in Prometheus. After various walk-on parts in Shakespeare productions at the Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park, London, she joined the Oxford Playhouse repertory company in 1940, playing, inter alia, “Margaret” in Dear Brutus and “Patty Moss” in The Two Bouquets. Kerr’s first film role was in the British production Contraband (US: Blackout, 1940), aged 18 or 19, but her scenes were cut. She had a strong support role in Major Barbara (1941) directed by Gabriel Pascal. Kerr became known in Britain playing the lead role in the film of Love on the Dole (1941). Said critic James Agate of Love on the Dole, “is not within a mile of Wendy Hiller’s in the theatre, but it is a charming piece of work by a very pretty and promising beginner, so pretty and so promising that there is the usual yapping about a new star”. She was the female lead in Penn of Pennsylvania (1941) which was little seen; however Hatter’s Castle (1942), in which she starred with Robert Newton and James Mason, was very successful. She played a Norwegian resistance fighter in The Day Will Dawn (1942). She was an immediate hit with the public: An American film trade paper reported in 1942 that she was the most popular British actress with Americans. Kerr played three women in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). During the filming, according to Powell’s autobiography, Powell and she became lovers:[12] “I realised that Deborah was both the ideal and the flesh-and-blood woman whom I had been searching for”. [12] Kerr made clear that her surname should be pronounced the same as “car”. To avoid confusion over pronunciation, Louis B. Although the British Army refused to co-operate with the producers- and Winston Churchill thought the film would ruin wartime morale – Colonel Blimp confounded critics when it proved to be an artistic and commercial success. According to Powell, his affair with Kerr ended when she made it clear to him that she would accept an offer to go to Hollywood if one were made. In 1943, aged 21, Kerr made her West End début as Ellie Dunn in a revival of Heartbreak House at the Cambridge Theatre, stealing attention from stalwarts such as Edith Evans and Isabel Jeans. “She has the rare gift”, wrote critic Beverley Baxter, of thinking her lines, not merely remembering them. The process of development from a romantic, silly girl to a hard, disillusioned woman in three hours was moving and convincing. Near the end of the Second World War, she also toured Holland, France, and Belgium for ENSA as Mrs Manningham in Gaslight (retitled Angel Street), and Britain (with Stewart Granger). Alexander Korda cast her opposite Robert Donat in Perfect Strangers (1945). The film was a big hit in Britain. So too was the spy comedy drama I See a Dark Stranger (1946), in which she gave a breezy, amusing performance that dominated the action and overshadowed her co-star Trevor Howard. This film was a production of the team of Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat. Her role as a troubled nun in the Powell and Pressburger production of Black Narcissus (1947) brought her to the attention of Hollywood producers. The film was a hit in the US, as well as the UK, and Kerr won the New York Film Critics Award as Actress of the Year. British exhibitors voted her the eighth-most popular local star at the box-office in 1947. [14] She relocated to Hollywood and was under contract to MGM. Kerr in Young Bess (1953). Kerr’s first film in Hollywood was a mature satire of the burgeoning advertising industry, The Hucksters (1947) with Clark Gable and Ava Gardner. She and Walter Pidgeon were cast in If Winter Comes (1947). She received the first of her Oscar nominations for Edward, My Son (1949), a drama set and filmed in England co-starring Spencer Tracy. In Hollywood, Kerr’s British accent and manner led to a succession of roles portraying refined, reserved, and “proper” English ladies. Kerr, nevertheless, used any opportunity to discard her cool exterior. She had the lead in a comedy Please Believe Me (1950). Kerr appeared in two huge hits for MGM in a row. King Solomon’s Mines (1950) was shot on location in Africa with Stewart Granger and Richard Carlson. [15] This was immediately followed by her appearance in the religious epic Quo Vadis (1951), shot at Cinecittà in Rome, in which she played the indomitable Lygia, a first-century Christian. She then played Princess Flavia in a remake of The Prisoner of Zenda (1952) with Granger and Mason. In between Paramount borrowed her to appear in Thunder in the East (1951) with Alan Ladd. In 1953, Kerr “showed her theatrical mettle” as Portia in Joseph Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar. [8] She made Young Bess (1953) with Granger and Jean Simmons, then appeared alongside Cary Grant in Dream Wife (1953), a flop comedy. Kerr departed from typecasting with a performance that brought out her sensuality, as “Karen Holmes”, the embittered military wife in Fred Zinnemann’s From Here to Eternity (1953), for which she received an Oscar nomination for Best Actress. The American Film Institute acknowledged the iconic status of the scene from that film in which Burt Lancaster and she romped illicitly and passionately amidst crashing waves on a Hawaiian beach. The organisation ranked it 20th in its list of the 100 most romantic films of all time. Having established herself as a film actress in the meantime, she made her Broadway debut in 1953, appearing in Robert Anderson’s Tea and Sympathy, for which she received a Tony Award nomination. Kerr performed the same role in Vincente Minnelli’s film adaptation released in 1956; her stage partner John Kerr (no relation) also appeared. In 1955, Kerr won the Sarah Siddons Award for her performance in Chicago during a national tour of the play. After her Broadway début in 1953, she toured the United States with Tea and Sympathy. Kerr in An Affair to Remember (1957). Black and white photo of Robert Mitchum holding a gun standing next to Deborah Kerr in the movie Heaven Knows Mr. With Robert Mitchum in Heaven Knows, Mr. Thereafter, Kerr’s career choices would make her known in Hollywood for her versatility as an actress. [1][13] She played the repressed wife in The End of the Affair (1955), shot in England with Van Johnson. She was a widow in love with William Holden in The Proud and Profane (1956), directed by George Seaton. Neither film was much of a hit. However Kerr then played Anna Leonowens in the film version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I (1956); with Yul Brynner in the lead, it was a huge hit. Marni Nixon dubbed Kerr’s singing voice. She played a nun in Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison (1957) opposite her long-time friend Robert Mitchum, directed by John Huston. It was very popular as was An Affair to Remember (1957) opposite Cary Grant. Kerr starred in two films with David Niven: Bonjour Tristesse (1958), directed by Otto Preminger, and Separate Tables (1958), directed by Delbert Mann; the latter movie was particularly well received. She made two films at MGM: The Journey (1959) reunited her with Brynner; Count Your Blessings (1959), was a comedy. Both flopped, as did Beloved Infidel (1959) with Gregory Peck. Kerr in The Sundowners (1960). Kerr was reunited with Mitchum in The Sundowners (1960) shot in Australia, then The Grass Is Greener (1960), co-starring Cary Grant. She appeared in Gary Cooper’s last film The Naked Edge (1961) and was in The Innocents (1961) where she plays a governess tormented by apparitions. Kerr made her British TV debut in “Three Roads to Rome” (1963). She was another governess in The Chalk Garden (1964) and worked with John Huston again in The Night of the Iguana (1964). She joined Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra in a love triangle for a romantic comedy, Marriage on the Rocks (1965). In 1965, the producers of Carry On Screaming! She replaced Kim Novak in Eye of the Devil (1966) with Niven, and was reteamed with Niven in the comedy Casino Royale (1967), achieving the distinction of being, at 45, the oldest “Bond Girl” in any James Bond film, until Monica Bellucci, at the age of 50, in Spectre (2015). Casino Royal was a hit as was another movie she made with Niven, Prudence and the Pill (1968). Pressure of competition from younger, upcoming actresses made her agree to appear nude in John Frankenheimer’s The Gypsy Moths (1969), the only nude scene in her career. She made The Arrangement (1969) with Elia Kazan, her director from the stage production of Tea and Sympathy. Concern about the parts being offered to her, as well as the increasing amount of nudity included in films, led her to abandon the medium at the end of the 1960s in favour of television and theatre work. [8] After her first London success in 1943, she toured England and Scotland in Heartbreak House. In 1977, she came back to the West End, playing the title role in a production of George Bernard Shaw’s Candida. The theatre, despite her success in films, was always to remain Kerr’s first love, even though going on stage filled her with trepidation. I do it because it’s exactly like dressing up for the grown ups. I don’t mean to belittle acting but I’m like a child when I’m out there performing-shocking the grownups, enchanting them, making them laugh or cry. It’s an unbelievable terror, a kind of masochistic madness. The older you get, the easier it should be but it isn’t. Kerr experienced a career resurgence on television in the early 1980s when she played the role of the nurse (played by Elsa Lanchester in the 1957 film of the same name) in Witness for the Prosecution, with Sir Ralph Richardson. She also did A Song at Twilight (1982). She took on the role of the older Emma Harte, a tycoon, in the adaptation of Barbara Taylor Bradford’s A Woman of Substance (1984). For this performance, Kerr was nominated for an Emmy Award. Kerr rejoined old screen partner Mitchum in Reunion at Fairborough (1985). Other TV roles included The Assam Garden (1985), Ann and Debbie (1986) and Hold the Dream (1986), the latter a sequel to A Woman of Substance. Kerr’s first marriage was to Squadron Leader Anthony Bartley RAF on 29 November 1945. They had two daughters, Melanie Jane (born 27 December 1947) and Francesca Ann (born 20 December 1951 and subsequently married to the actor John Shrapnel). The marriage was troubled, owing to Bartley’s jealousy of his wife’s fame and financial success, [10] and because her career often took her away from home. They divorced in 1959. Her second marriage was to author Peter Viertel on 23 July 1960. In marrying Viertel, she became stepmother to Viertel’s daughter, Christine Viertel. Although she long resided in Klosters, Switzerland and Marbella, Spain, Kerr moved back to Britain to be closer to her own children as her health began to deteriorate. Her husband, however, continued to live in Marbella. Stewart Granger claimed in his autobiography that she had approached him romantically in the back of his chauffeur-driven car at the time he was making Caesar and Cleopatra. [18] Although at the time he was married to Elspeth March, he states that he and Kerr went on to have an affair. [19] When asked about this revelation, Kerr’s response was, What a gallant man he is! Kerr died aged 86 on 16 October 2007 at Botesdale, a village in the county of Suffolk, England, from the effects of Parkinson’s disease. [21][22][23] Less than three weeks later on 4 November, her husband Peter Viertel died of cancer. At the time of Viertel’s death, director Michael Scheingraber was filming the documentary Peter Viertel: Between the Lines, which includes reminiscences concerning Kerr and the Academy Awards. [25] She is buried in Alfold Cemetery, Alfold, Surrey. Love on the Dole. The Day Will Dawn. A Battle for a Bottle. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. I See a Dark Stranger. King Solomon’s Mines. Thunder in the East. The Prisoner of Zenda. From Here to Eternity. The End of the Affair. The Proud and Profane. The King and I. Singing dubbed by Marni Nixon. An Affair to Remember. The Grass Is Greener. The Night of the Iguana. Marriage on the Rocks. Eye of the Devil. Prudence and the Pill. ITV Play of the Week. Episode: Three Roads to Rome. Episode: A Song at Twilight. Witness for the Prosecution. A Woman of Substance. Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway. The Day After the Fair. Long Day’s Journey into Night. Ahmanson Theatre, Los Angeles. A Date with Nurse Dugdale. BBC Home Service, 19 May 1944. Guest star role in the penultimate episode. King Solomon’s Mines[27]. The Pleasant Lea[28]. Michael and Mary[29]. The Colonel’s Lady[30]. She is tied with Thelma Ritter and Amy Adams as the actresses with the second most nominations without winning, surpassed only by Glenn Close, who has been nominated eight times without winning. British Academy Film Awards. Outstanding Supporting Actress – Limited Series. Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama. Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. Henrietta Award (World Film Favorite). The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Love on the Dole. Black Narcissus, I See a Dark Stranger. The King and I, Tea and Sympathy. Kerr’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1709 Vine Street. Kerr was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1998, but was unable to accept the honour in person because of ill health. [31] She was also honoured in Hollywood, where she received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1709 Vine Street for her contributions to the motion picture industry. Although nominated six times as Best Actress, Kerr never won a competitive Oscar. In 1994, Glenn Close presented Kerr with the Honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement with a citation recognising her as “an artist of impeccable grace and beauty, a dedicated actress whose motion picture career has always stood for perfection, discipline and elegance”. Kerr won a Golden Globe Award for “Best Actress – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy” for The King and I in 1957 and a Henrietta Award for “World Film Favorite – Female”. She was the first performer to win the New York Film Critics Circle Award for “Best Actress” three times (1947, 1957 and 1960). Although she never won a BAFTA or Cannes Film Festival award in a competitive category, both organisations gave Kerr honorary awards: a Cannes Film Festival Tribute in 1984[33] and a BAFTA Special Award in 1991. In September and October 2010, Josephine Botting of the British Film Institute curated the “Deborah Kerr Season”, which included around twenty of her feature films and an exhibition of posters, memorabilia and personal items loaned by her family. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Autographs\Celebrities”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, South Korea, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Republic of Croatia, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam.

Categories: deborah

Related Topics: autographed, deborah, detailed, handwritten, kerr, letter, personal, signed